I am a man and that means I am a combination of two very different animals: I am at once the father of my son, and the child of my parents. One of these two will have been in charge for most of the day.

Baseline motivation can be the most defining quality of personality, the most enfeebling or the most empowering. While it is generally accepted that motivation produces and regulates goal-directed behaviour, the following examines the validity of that assumption, making a distinction between the necessarily goal-related nature of cognition-mediated motivation and that of baseline motivation as a global modulatory system regulating behaviour and awareness. An example might be in the energised behaviour of the parent bird feeding her chicks, where a consistently high baseline level of global motivation modulates each instance of instrumental motivation involved in the task of leaving the nest, finding food and returning, a demanding business repeated throughout most of the day with undiminished vigour. In contrast, abnormally low levels of baseline motivation are typically associated with chronic depression. In the laboratory, manipulation of approach/avoidance motivation necessarily assumes goal-directed motivation over the time window of the experiment. The hierarchical nature of motivation, however, allows for the presence of a baseline level of motivation independent of the instrumental motivation under study, and persisting over an extended timeframe. Research at the biological level has proposed tonic dopamine release as being implicated in maintaining baseline levels of motivation. The persistence of the ‘goal-directed’ assumption, however, may be precluding a conceptualisation of the mechanism of baseline motivation and thus eliminating an avenue of research into a non-trivial factor in human behaviour.

The word ‘motivation’ carries the implicit assumption that it refers to something that drives our own behaviour – we might say that an athlete’s success was due to her motivation, specifically, her baseline motivation – but we are equally (and habitually) capable of being motivated to elicit or influence the behaviour of others for our benefit. This concept of a mechanism for ‘passive motivation’ is central to the model. In the following, I propose firstly the co-existence, in the normal personality, of both active and passive motivation, and secondly, that passive motivation (i.e., motivation to elicit or influence the behaviour of others) serves a distinct neurological function, having its roots in the infant personality. I further propose that the mechanism of baseline motivation is distinct from the “reward circuit”, and that it comprises rather a corticothalamic dopaminergic system coding for a variable representing the urgency of action.

At the most basic level, we might consider baseline motivation to be subserving homeostasis: the need to find food, shelter and to be alert to danger. Unlike the adult which is capable of serving these needs by its own action, the infant’s motivation references not its own action but the action of the carer. It is proposed that the “passive” system modulating motivation to elicit the action of the carer is necessarily distinct at a cognitive level from that of the mature personality where baseline motivation drives the individual’s own behaviour: the adult baseline system situates the individual as the subject, the originator of action, whereas the infant personality is situated as the object, as the recipient or beneficiary of the actions of its carers.

The model rejects the assumption, valid in the case of instrumental motivation, that the degree of baseline motivation is a matter of its intensity, and proposes that baseline motivation is the output of a cognitive variable derived from the processing of the urgency of action. It further proposes the co-existence of passive and active baseline motivation in the normal personality as a mechanism having a direct bearing upon the individual’s capacity for narcissistic behaviour.

passive motivation

In speaking of “passive motivation”, the meaning here is literal, no more than that. As reflected in English grammar, the nature of action is two-fold:

Active: the police push the activists back

Passive: the activists are pushed back by the police

Passively-motivated behaviour is a commonplace phenomenon such that, on one level, it is a matter of putting a name to something with which we are all familiar. Put at its simplest, passive motivation works to produce or influence, for your benefit, someone else’s behaviour, rather than your own. It might lead merely to bragging, seeking to impress, or some might tend to ingratiate themselves with a superior at work, but it’s a matter of degree. Abusive, manipulative relationships, though complex in their psychological origins, are manifestations of passive motivation. We tend to focus on the details – the gaslighting, guilt-tripping, deception, transference of blame etc. – and yet a common thread lies in the underlying motivation to influence or control the behaviour of the victim for the benefit of the manipulator.

It might be tempting to argue that manipulating others is simply another way of achieving one’s goals but this suggestion fails in the parsimony it strives for; it attributes a degree of sophistication to the infant personality that would be quite inexplicable.

The central question is this: am I invariably the subject in my motivation or might I sometimes be the object, the intended recipient and beneficiary of someone else’s action? Is my motivation, at this moment, active, or do I, with this behaviour, really just intend to promote the odds of nice things happening to me? The significance of this question lies in the proposition that some largely grow out of the habit of passively-motivated behaviour while others do not; it’s not only dimensional, it’s developmental.

For those who would prefer to follow the chronology of an idea as it developed, the section below on “intellect type” sets out the ideas that led eventually to the main theory, i.e., the conflict of active and passive baseline motivation in the normal personality. It also adds a layer of complexity that only muddies the waters at this stage. In summary, I believe it can be shown that, in the context of motivation, two intellect types – root intellect and branch intellect – are evident. As I’ve said, at this point, I think it is a distraction to go into this in any depth. The (past-oriented) root intellect type tends to understand events and motives in terms of their causes, while the (future-oriented) branch intellect tends to rationalise these events in terms of their intended goal. That, I think, is enough said for the moment. The hypothesis has its origins in but is not premised upon this typology and I think it’s best introduced without this de facto layer of potential confusion.

intellect type

I believe it can be shown that, in the context of motivation, two intellect types – root intellect and branch intellect – are evident.

To introduce the basis for proposing this intellect typology, we can take a fresh look at a belief that passed for science back in the days of Freud and Jung. It’s interesting to see how we got here and how easily a crucial insight that could have informed research can be overlooked or forgotten because of poor terminology.

Freud & Co. often argued about their patients and how to interpret their symptoms. Hidden in plain sight in the preface to “Psychological Types” (Vol. VI in the Collected Works), is arguably one of the most insightful elements of Jung’s entire commentary on the subject. It is here that he recounts the observation that gave rise to his theory of Extraversion and Introversion: it was one of those disagreements. Freud and Adler were arguing about a patient whose “hysteria” Freud attributed to events in her past, but Adler was sticking to his guns: yes, of course, she has some repressed memories but Freud was completely missing the point: what was really going on here was that she had discovered a way of getting power over her husband. Jung was watching this interminable debate going nowhere, but what he was thinking about was the argument itself.

Jung’s original concept of Past/Future Intellect Orientation

Jung had become aware of something that he found intriguing and it stemmed from his realisation that Freud and Adler might be imposing their own personality type upon the patient. The entirety of Freud’s argument referenced events in the patient’s past. Everything Adler countered with related to her aim to achieve something in the future. Jung’s first thought was that he seemed to be looking at some kind of past/future intellectual orientation, a tendency that neither Freud nor Adler seemed able to shake off.

He found the idea so compelling that he tasked himself with the search for an explanation. Jung hypothesized what he called “object fixation” as an explanation for Freud’s apparent preoccupation with past causes and origins. He dismissed the possibility of Freud’s evident intellectual past-orientation being perhaps some kind of strongly-reinforced trait or even an innate intellectual tendency. By proceeding to question what lay behind the phenomenon I believe Jung made an error in logic, mistaking the principle for the derivative. This, nevertheless, was the foundation for his now well-known theory of extraversion and introversion.

So, why waste time on this? What it appears to amount to is just Jung’s surmise about an argument that seems to the modern mind more likely to have had no significance at all. On the one hand, we have the proposition of some kind of past/future intellect orientation and then, almost mysteriously, we seem to be discussing extraversion and introversion, whatever that really means, and both propositions living happily together in a vacuum of evidence. Why even mention it?

The early psychologists were, of course, working almost completely in the dark. Some of their beliefs were, to be blunt, simply nonsense, and few more so than the notion of psychic energy. Jung’s “extraversion and introversion” were the terms he coined to describe the direction – outward or inward – of this “psychic energy”. While his terms have survived in some fields, their original meaning is now altogether lost, and for the rather persuasive reason that psychic energy has long since been proven not to exist.

It is sometimes argued that the idea of psychic energy was no more than a working metaphor, but that doesn’t really hold up; they believed in its existence. In physics, the theory of the conservation of energy had been transformative, and the early psychologists felt they needed something of that nature to help put their work on a scientific footing. Some individuals clearly had immense resources of “energy”, throwing themselves vigorously and tirelessly into their work whereas some others were inexplicably lethargic. The obvious answer, psychic energy, was borrowed from physics, and the convenience of it proved tragic for the infant science, not just because it was wrong but because, I hope to show, it was so nearly right.

Most interestingly, libido – generally taken to mean sexual drive – and psychic energy were sometimes used synonymously, and so while the idea of extraversion or introversion of the libido made sense to Jung, Freud’s writing of that period presents libido as a well of psychic energy, and having no “inward” or “outward” component. Toward the end of his life, Freud came to view libido as being a bi-directional affair, but his new model was still radically different from Jung’s: Freud latterly promoted the idea of a positive-negative conflict: a life drive and a death drive.

- The Jungian theory of libido gave us two personality types: the extravert (outwardly-directed libido) and the introvert (inwardly-directed) – neither one any “better” than the other – just different – one tending to be more outgoing, the other more reserved.

- Late Freudian libido theory introduced a much more serious proposition: a positive and a negative flow of energy – one life-giving, creative, and the other a drive for death and destruction, echoes of God and the Devil.

The Jungian and Freudian theories of libido appeared, therefore, destined to remain utterly incompatible, and ultimately, seemingly irrelevant to science.

Again, why waste time on this? We know that psychic energy does not exist so what could possibly be interesting about a disagreement regarding its mechanics? Jung filled a fairly weighty volume with the answer to that question, devoting chapters to defending his belief in psychic energy, not in a modern empirical sense but by citing his experience as a psychiatrist. The problem, I hope to show, lay not so much in the impossibility of justifying their beliefs but in the limitations of the concepts then available to them. In particular, they had no access to the neuroscience concept of a variable. I’ll return to this, but for the moment, let me continue the thread of Jung’s past/future intellect orientation.

motives of the “terrorist”

(Apologies for writing in the first person. I’ll try to be brief).

A long time ago, I got into an argument about the IRA and the violence in Belfast. In the course of that argument, an extraordinary thing happened: I caught a look which told me that the other man thought he was talking to a complete fool.

His (Adlerian – goal-focused) argument centred on the imagined ambitions of the Catholic minority. Given the chance, he insisted, they would do everything they could to disempower and drive out the Protestant majority in the North of Ireland. On the other (Freudian – cause-fixated) side, I found it hard to get past the history. I saw Republican resistance as a natural consequence of the cruelty and injustice of British colonial rule. I was listening to this man adduce fact after fact to prove the anti-Protestant intent of the Catholic minority and then I catch a look that tells me that he thinks I don’t have what it takes to follow his argument. The irony astonished me!

What, at essence, we were discussing were the motives behind the then-ongoing “terrorist” attacks. But, sparked by that look, what was really focussing my attention was not the argument itself but a sense of an underlying difference in our fundamental approach to the subject: the consistency with which I had been presenting a past-related explanation for the actions of the IRA and a consistency in the counter-argument presenting a future-related attribution of what they wanted to achieve, their aim to disempower and expel. And that was what he thought I was failing to understand. Each time that he put forward his reasonable argument regarding the aims and ambitions of the Catholic minority, I had failed to address it in the terms in which it was presented. He mistakenly believed I wasn’t understanding what he had to say but I had been making exactly the same mistake, and presenting historical fact and context as if that alone was all that mattered.

This was not a five-minute argument and yet the consistency was 100%. Increasingly, I came to suspect that this was more than just an argument from polarized positions on the armed struggle; it was more and more like an argument between two completely incompatible types of intellect.

What it came down to, on my part, was an instinctive tendency to assume motivation ultimately to be explicable not in terms of its goal but in terms of its origin, its cause. I saw the motivation of “the terrorist” as a product of his experience and of the injustice that he had seen, first-hand, inflicted upon his community. My feeling was that his motivation – his commitment to the cause – arose, in large measure, from his empathy with his community, the oppressed victims of the British and the loyalists. But this cause-oriented attribution has no resonance for someone for whom the aim or goal of every action is instinctively proposed as an explanation: the terrorist, consumed by an irrational hatred of the established order, is intent on spreading suffering, death and destruction. Bear in mind that the question at this stage relates to my own intellectual tendency, as distinct from an academic framing of behaviour in terms of cognition and motive.

Some years later, I read Carl Jung’s “Psychological Types” and his account, in the preface, of that argument in which Freud seemed to understand behaviour only in terms of its cause while Adler seemed able only to frame it in terms of the goal. I would have, as I imagine many others have done, passed over Jung’s account of the backstory of his extravert/introvert theory without any genuine depth of interest had it not been for my own experience. In the event, I knew exactly what he was talking about; I was primed to give it credence and found myself concurring with his apparent conviction that this communication problem was telling us something about how the brain processes information relative to motivation. Unlike Jung, however, I had, at that time, neither the wish nor the wit to look deeper. I simply and naively accepted, to my own satisfaction, the likelihood, particularly with respect to motivation, of there being two intellect types: past and future-orientated.

Freud’s intellect (and intellectual aptitude) was, I premise, fundamentally past-oriented (which might be termed root-intellect) while Adler was, equally unmistakably, future-oriented (branch-intellect). The utility of this proposition will, I hope, become clear.

(Please feel free to ignore this paragraph. I don’t have the talent to fix it but some folk may be able to thole it). I mentioned earlier that I believe Jung made an error in logic. I think it’s worth noting that Jung’s “subject/object” concept of introvert and extrovert differentiation discussed perception rather than action, i.e. the subject is aware of the object and attributes a certain relative value or importance to it. But the concept of extroversion is, of course, meaningless without reference to the libido, and the concept of the libido assumes that the relationship between subject and object is not inert. If the libido is object-directed, it cannot be a matter of mere awareness. The relationship must have reference to the potential, either active or passive, of action, in the widest sense. Perception, in this context, is, I believe, relevant to the psyche only in as much as it is prerequisite to action. The possibility, potential, or intention of action of the subject upon the object or of object upon subject (which we might term passive potential) is, I think, what is of concern to both types, the “root-intellect” type requiring, at the most fundamental level, to conceptualize action in terms of cause, the “branch-intellect,” in terms of its potential or intended results. The apparent importance which the two types attach to either subject or object is, if that is the case, a consequence of the two interpretations of that which is the principal concern of the psyche: the potential actions and events which either actively or passively relate subject and object. That is to say, the observed intellectual orientation is, in fact, the reason for the extrovert/introvert differentiation which Jung hypothesised to explain it.

Root Intellect and Branch Intellect

The premised past-oriented intellect is typified by the tendency and aptitude to get to the root of the issue. It will always tend to focus upon cause. Where there is a need to understand, it is in terms of the radical. Does the mind tend to the radical; does it focus upon the root of the issue; is the aptitude root and cause related? These tendencies and aptitudes are suggestive of the past-oriented intellect – the root intellect. It follows also that, for the root intellect, a high score for root/cause aptitude should be accompanied by a negative score for branch/goal aptitude.

The less-common future-oriented branch intellect is typified by the tendency and aptitude to extrapolate and to deal with the goals, aims, consequences and ramifications of the issue. There is frequently a marked tendency to be observant, to absorb, without effort, a proliferation of detail. That facility has, I suspect, cascaded from the distinct core ability and tendency to extrapolate, to consider the consequences of an event, the ramifications. For the branch intellect, actions are instinctively rationalised in terms of their goals.

The part that this differentiation plays will become apparent although the model I’m about to set out is not premised upon it. If anything, it is the existence of this differentiation that has helped muddy the waters, with both the (less-healthy) passively-motivated root-intellect and the (healthy) actively-motivated branch-intellect being identified as introvert personalities.

Intellectual orientation is, I suspect, immutable; there is little traffic between the Freudian and Adlerian schools. I think the Freudian psychologists may provide a ready-made pool of past-oriented intellect and, likewise, the future-orientation of the Adlerians pervades all of their work. These two groups should help refine testing for a more diverse population.

Intellect Type

| Orientation | Type | Focus | Aptitude |

| Past | Root Intellect | source; cause: origin | Convergent: to reduce to the fundamentals, the radical |

| Future | Branch Intellect | goals; aims; consequences | Divergent: to extrapolate; to see ramifications |

the age of narcissism and entitlement

Why does a baby cry? It is, of course, because it is incapable of satisfying its needs by its own action. It has an instinctive and subsequently-reinforced sense of entitlement to have its needs satisfied by the action of the carer: “feed me – comfort me – reassure me of my security.” The cognitive process underlying the infant’s motivation blurs the distinction between the internal and external world, with the satisfaction of needs requiring and assuming the agency of the carer. This is passive motivation in its purest and most natural form, but thirty years later, that same degree of narcissism, manipulation and entitlement persisting in the adult personality would be considered pathological.

If the model is valid, however, the system mediating passive motivation does persist to some degree in the adult personality – the active and passive systems co-exist. Baseline motivation is hypothesised to be not simply a matter of gain or intensity, but the net output of these two conflicting systems. The obvious question as to why we should propose two coexisting systems of motivation when one would seem to suffice to explain behaviour was answered many years ago by Abraham Maslow when he stressed the importance of research focusing upon what he termed the self-actualising personality. When we restrict research to the study of the normal personality, the levels of baseline motivation that we can infer seem to suggest that baseline motivation has a minimal impact upon behaviour. This is true only of the normal personality. The motivational conflict of the normal personality renders motivation levels comparatively weak and indistinct. It is an enfeebling, “vector” conflict ensuring that, for the normal personality, the immense motivational potential of the individual is never remotely reached or even imagined.

commitment

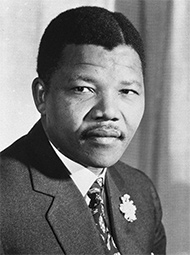

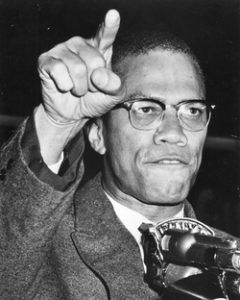

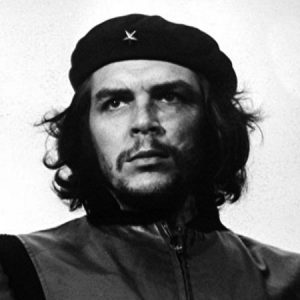

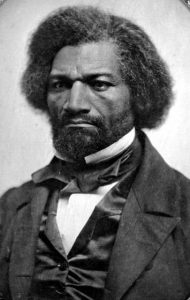

We instinctively venerate some individuals, not just for their talent or their intellects but for their actions and their level of drive and focus, their commitment to serving needs external to their own. Motivation is the distinguishing feature of exceptional personalities like Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass and Che Guevara, aptly described by Franz Fanon as “the world symbol of the possibilities of one man”. Rather than probe the confusion of the conflicted, relatively weak and thus relatively obscure baseline motivation of the normal personality, we should look, firstly, at those individuals – Maslow’s self-actualising personalities – whose unusually high levels of active and correspondingly low levels of passive motivation would place them at the far reaches of the normal distribution.

It’s almost a redundant statement but it is the degree of personal commitment to the cause or goal which determines the level of baseline motivation, the outcome, in the rare case of complete commitment, being virtually unconflicted motivation, an exceptional level of drive, focus and consciousness. The significant difference between Mandela and the rest of humanity was, of course, his complete commitment to the cause:

That degree of commitment is sufficiently rare as to lie entirely outside of the experience of most psychologists (Maslow being the obvious exception) but it is recognition of the absence of motivational conflict characterising the completely-committed personality that provides the first hint of the enfeebling nature of the highly-conflicted motivation of the normal personality in the infantilizing milieu of an individualistic western consumer culture.

In contrast to those highly-motivated altruistic personalities, we can also consider their opposites: the highly-motivated narcissists. Donald Trump is an exemplar. At every turn, Donald Trump betrays a disturbingly unremarkable intellect. It is his motivation, his focused self-obsession and his relentless egoistic drive that mark him out as head and shoulders above all those around him. His entire history speaks of a degree of egoistic motivation that is mercifully extremely rare. His lack of conflicting motivation could hardly be more obvious. That is his “strength”. He is unreservedly committed to the welfare of Donald Trump – a paragon of a fully-grown adult with the passive, manipulative motivational vector of an infant.

romantic love – a motivational state

A more familiar form of commitment is romantic love. This model posits “love” as the instinctive drive simply and literally to care for and be committed to the welfare of the other person. However much affection we might feel for them, we love our children to the extent that we are committed to their welfare. This is the very essence and origin of the systems of active and passive motivation. As a pair-bonding species with offspring that are slow to mature, we evolved the capacity to love because survival required that we are committed to caring for each other and for our children. We tend to discuss (and even research)! love from an experiential perspective or in terms of attachment, but much more pertinent and explanatory is the underlying radical motivational transformation: the infantile, passive, self-focused vector is effectively reversed, giving way to a personal commitment to the welfare of the other person. Naturally, we romanticise it, but love, as distinct from the most visceral lust and the deepest affection, can be defined as a transformative motivational state arising from an instinctive personal commitment to the welfare of another person, and anyone who has been in love has had a taste of the life-changing phenomenon of relatively unconflicted active motivation.

Survival of the family and of the community places certain obligations upon its members. The healthy parent is instinctively aware that the needs of the family must take precedence over the desires of the individual. Weakness, however, breeds weakness. The unhealthy parent tends to impede motivational development in the child by placing insufficient emphasis upon encouraging empathy and considerate, unselfish behaviour both by instruction and, more importantly, by example. The selfishness of the individual in one situation emerges as an equivalent weakness or inadequacy in another. The exception proves the rule, but the child which is exposed to the extreme selfishness of its parents can generally be expected to follow in their footsteps and, perhaps, eventually treat us to the joys of his narcissistic personality disorder. Depending on the depth of his pain, he may achieve some local notoriety as a sociopath. As long as we fail to recognize the simplicity – the direct relationship between selfishness and motivational immaturity – we lack sufficient understanding to tackle the underlying sickness at source.

global motivation: a variable

Assuming the existence of baseline motivation as a neurological mechanism, let’s try to be clear about what’s meant by the term. An article by Jim Taylor in Psychology Today gives probably as good a definition as any, albeit through a suspiciously success-oriented lens. He asks, “Why is the relationship between motivation and success so robust? Because high motivation will ensure total preparation which will, in turn, ensure maximum performance and results.” He goes on to define motivation in familiar, accessible terms.

“Motivation can be defined in the following ways:

- An internal or external drive that prompts a person to action

- The ability to initiate and persist at a task

- Putting 100% of your time, effort, energy, and focus into your work

- Being able to work hard in the face of obstacles, boredom, fatigue, stress, and the desire to do other things

- Motivation means doing everything you can to be as productive as you can.”

At the behavioural/counselling end of psychology, the existence of baseline motivation is no more in question today than it was in the days of Freud and Jung, and their insightful, confused debates over the mechanics of libido. It is when we get to research at the biological level that we find a limited focus on the subject, one reason being that we are discussing a variable that has not, as yet, been isolated or even proposed. To put it bluntly, the fact that ‘psychic energy’ does not exist has persuaded generations of academics that, ergo, libido is a flawed, archaic construct. We have long since passed the point at which a discussion of the mechanics of libido would raise anything more than derision in the scientific community. Equally important, how could we possibly research the neural correlates of such a woolly concept? The challenge, therefore, is to make sense of baseline motivation as a neurological mechanism. And I believe we can now do exactly that. It is recognised that tonic dopamine release can modulate the gain of instrumental motivation, but the underlying cognitive systems regulating extracellular dopamine levels in the infant and adult personalities remain to be elucidated.

The model tells us that we’re discussing a mechanism that has evolved over millennia, something that had its beginnings a few hundred million years ago, suggesting that the key to understanding motivation as a neural function may lie in the evolution of “action” itself, and we already know more than enough about that to trace its development with some confidence, even if armed with no more than a nebulous notion of the evolution of some imaginary creature in our Devonian ancestry.

Apologies if the following comes across as a series of just-so stories. I think it’s worth taking the time to move through and beyond the traditional accounts of primitive life in order, hopefully, to demonstrate that there is almost an element of inevitability in the evolution of motivation and consciousness.

evolution of locomotion

We might consider, firstly, the development of regulated locomotion, allowing a minimal expenditure of energy during foraging, and a maximum release of energy in reserve for escapes. Locomotion is thus capable of serving as a stimulus response to, for example, olfactory cues indicating the proximity of a predator. However, while survival will tend to favour the creature that has evolved that threat response, it’s still a grossly inefficient behaviour: it means bursts of release of unattenuated energy and yet, of course, at this level of existence, conservation of energy is everything.

motion detection and time

We now arrive at the point at which the inextricable relationship between motivation and time becomes clear. Consider the survival advantage of the prey that has evolved the facility of responding not only to proximity but to perception of movement, and this leading ultimately to an evaluation, however imperfect, of the approach velocity of the predator. This entirely novel information is highly adaptive in that it translates into an evaluation not of the spatial proximity of the predator but of the temporal imminence of the attack. This is obviously a quantum leap forward in sophistication but it is still a stimulus-response. And we know it happened; it’s a capability common to all vertebrates.

The arms-race nature of prey/predator evolution leads inexorably to selection pressure not only for spatial proximity and motion-detection responses but ultimately for the supreme efficiency of attack-imminence response. This, however, involves a completely novel type of perception and processing: in order to provide an input that can evaluate to attack imminence, the approach of the predator has to be perceived and processed over time. And that is what is most salient about this processing: it requires both a data-stream of perception and an internal “clock” or oscillator. But this represents a massive leap forward in survival advantage.

Crucially, initiation of escape has become contingent upon time. It is the temporal imminence of the threat, rather than its spatial proximity, that has now become the dominant survival-critical issue: a predator closing in at speed represents imminent danger. The spatial proximity of the predator is a crude and inefficient trigger in comparison.

evolution of the urgency variable

The game-changing significance of this perception data-stream processing is that, because it is evaluating the temporal imminence of the threat, the creature is now triggering escape contingent upon the urgency of action. The prototype of what we describe as “motivation” has effectively come into being in the form of a data-stream-derived variable: urgency. There may be no trace of it in the fossil record but this facility to initiate and regulate locomotion in response to the urgency of action can only have conferred a major step change in survival advantage both in terms of escape outcomes and in terms of conservation of energy.

The data-stream-based urgency variable is also the optimum moderator of the energy released to locomotion. Not too far down the line, we are discussing a creature (an ancestor) that can conserve energy and life by modifying its own speed and direction in a pursuit context in response to a data-stream perception of a dynamic threat. Locomotion is initiated and regulated according to an ongoing assessment of the imminence of the threat and therefore the urgency of action. This is a highly complex sequence of data-stream-based calculations and of note should be the fact that we are now discussing a plausible ancestor of consciousness, one having a definition not far removed from the more concise of modern attempts: the ongoing processing of time and perception to initiate and moderate action.

In short, I believe I am on solid ground in proposing that the progenitor of animal “motivation” and consciousness was this facility to calculate and be responsive to the urgency of action.

Evolution rarely just casts something away if it’s still doing its job well; it builds upon it, integrates it with new structures, finds new uses for it. Conscious agency requires that effort be quantified globally – a level of baseline motivation is typically sustained over an extended, complex series of actions. The probability, throughout our subsequent evolution, of the persistence of that single variable, urgency, globally moderating effort and awareness, is far from being an untenable inference.

Human motivation, the urge to act, is sometimes described subjectively as having an “intensity” but, programmatically, neurologically, it is, I submit, the ongoing calculation of the urgency of action that regulates effort globally. Obviously, many tasks involve cognitive, conscious control over effort but, upstream of that, as Jim Taylor’s article suggests, effort, whether physical or intellectual, is regulated unconsciously, globally, and that global “motivation” variable is, I submit, urgency. The ancient Chinese philosophers called it “Chi”. Jung and Freud called it libido or psychic energy. Bowlby called it nonsense.

motivation – the candidate neural substrates

So, how might we approach the search for the neural substrates of an urgency variable? Where in the brain should we expect to find the system coding for it? Much of the research into motivation at the biological level investigates instrumental approach/avoidance motivation. It is more difficult to find work that sheds light on the system coding for baseline motivation, and I’m afraid the following effort at homing in on candidate anatomy is liable to undergo revision; it represents my current understanding.

At the most basic level, the model suggests that manipulation of extrinsic urgency may result in modulation of signalling detectable in multiple cortical regions. Correlating with an increase in perceived urgency, we might also expect to see an increase in activation at a functionally-central locus where there is early access to the visual datastream and where the highly-distributed nature of the proposed role of modulation at a global level is feasible. I suspect that such a characterisation may point to a dopaminergic system that involves the thalamus.

The thalamus has traditionally been viewed as a “hub” or relay station. It has also been proposed as the mediator of “temporal coherence” (Llinás, Ribary, Contreras and Pedroarena, 1998) thus providing a plausible basis for coherent consciousness, but it seems not unreasonable to speculate that part of its role may be that of a controller, a global regulator of motivation, awareness and attention. The hypothesised processing of urgency requires a system capable of evaluating a datastream of perception against a measurement of time at short scales. The thalamus is anatomically and functionally well-placed to process both perception and time: the oscillatory activity of thalamocortical neurons provide a plausible mechanism for short-scale time measurement, and of course, both the visual and auditory datastreams are routed through the thalamus. Interestingly, the one system that does not seem to pass through the “hub” is the olfactory system, and if you recall my just-so story of the evolution of the variable, it is only the visual and auditory data streams that can carry the information necessary to facilitate encoding of temporal imminence; the olfactory signal synapses instead on the olfactory bulb and goes straight to the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus where it can trigger the more primitive spatial-proximity-based fear response.

Another potentially interesting area of research is the thalamic role of the neuromodulator dopamine. Research has traditionally focused on dopamine as being implicated in reward-directed behaviour with, for example, drugs that block dopamine receptors reducing an animal’s motivation to engage in reward-generating behaviour. Regulation of motivation is a component of the reward system but, even within the confines of the behaviourist paradigm which still informs so many research methodologies, dopamine has also been shown to be a component of aversive behaviour. Phasic dopamine levels are typically observed to spike in anticipation of reward but it seems feasible that that “anticipation” spiking would be evident if a role of dopamine is regulation of motivation in preparation for the action expected to precipitate the reward.

A 1998 paper (Berridge and Robinson) posits the role of dopamine in some contexts as a component of the reward system but modulating motivational value “in a manner separable from hedonia and reward learning”. They employ the term “incentive salience” and this, if not quite a synonym, is a much better fit for the potential role of a corticothalamic dopaminergic system in coding for urgency.

Both the Freudian and Jungian concepts of libido were based upon the recognition of the ubiquitous phenomena associated with urgency. The early psychologists, however, and naturally enough, described it as “psychic energy” and that mistake, combined with Bowlby’s discovery of a more apt metaphor for mental activity in the logic circuits of early electronic control systems, was enough to lead him and others subsequently to discard Freud’s and Jung’s psychodynamic theories as worthless. Bowlby might have taken a different tack had his electronic switchgear control systems been capable, like modern computers, of processing a data stream. But the dogma of static-logic functionality took root, and from that departure, going forward, any meaningful study of the mechanism of motivation based upon its manifestly dynamic nature was rendered next to impossible.

Freud had speculated counter-intuitively that a drive to death and destruction is an element of the normal personality and he saw that drive as being unaccountably in conflict with a healthy drive to life. I believe the time-based construct of the urgency variable reveals the mechanism, and in this regard, the crucial aspect of the human psyche is that we are born helpless. The infant human, dog, horse, bird or elephant instinctively expects to be cared for. Instinctively, it rightly assumes that it is entitled to have its needs satisfied by the actions of those around it. The role of urgency is revealing, therefore, because the infant’s urgency is of a very special nature in that it does not reference its own action; it is manipulative, referencing the action of the carer.

the conflict of active and passive urgency in the normal personality

Identifying the passive nature of infant motivation is, I believe, key to understanding adult narcissism and the mechanics of baseline motivation in the adult personality. If the model is valid, there coexists, in the normal personality, a silent conflict of active and passive urgency subsequently expressed cognitively in motive and choice. What’s going to happen to me? What will I get out of this? What do people think of me? The logic of these considerations might seem beyond question, but the reality is that while for one individual, “what will I get out of this?” might be the first consideration, for another, in just the same circumstance, it might be the last. The construct of the conflict of active and passive urgency rejects the behaviourist and frankly schoolboy-like assumption of the universality of self-gratifying motives.

the cognitive basis of empathy

The model frames empathy as a survival-critical cognitive facility of parenthood, the facility to “feel” some representation of the infant’s urgency. It is, at least in part, because of the (healthy) parent’s capacity for empathic motivation that the infant’s communication of its own egoistic urgency can trigger, on the part of the parent, an appropriate measure of motivation to attend to the infant’s needs. Parenthood is, I believe, the root psychological basis of empathy, compassion and altruism.

narcissism and the egoism-altruism spectrum

narcissism and the egoism-altruism spectrum

The infant’s de facto lack of responsibility, its characteristic narcissism, its lack of empathy, its instinctive and valid sense of entitlement, and its passively-motivated manipulative behaviour are all natural, healthy and essential for survival. It is only unhealthy and detrimental to society when these characteristics strongly persist and prevail in adulthood.

This model proposes that:

- the data-stream-derived urgency variable lies at the core of the neurological mechanisms of motivation and consciousness

- consciousness, in its minimal form, can be defined as: the ongoing processing of time, perception and introception to initiate and regulate action

- the normal personality lies on an egoism-altruism spectrum: urgency can sustain simultaneously both a passive and an active component

- and the reason being that life has two-stages: childhood and parenthood.

I think I can now repeat the statement made in the introduction and, hopefully, it now carries more meaning:

I am a man and that means I am a combination of two very different animals: I am at once the father of my son, and the child of my parents. One of these two will have been in charge for most of the day.

Through whose eyes do I see the world? With whose mind do I understand – the child or the man? I keep coming back in my mind to the Israel-Palestine “conflict” (a disgustingly inappropriate term for indigenous resistance to settler colonialism, ethnic cleansing, decades of military occupation, oppression and apartheid). In July 2014, Israel was once again inflicting a murderous collective punishment of grotesquely disproportionate force upon the Palestinians they have imprisoned and besieged in the Gaza strip – over 2,100 dead – babies to grandparents – two thousand one hundred human beings, extinguished – calculated physical and psychological trauma on a scale utterly unimaginable. The message was simple: “fear us; we are very powerful, and we will act without restraint; Hamas has brought this upon you.”

With whose mind do the architects of this carnage understand – the child or the man? Freud recognised the death drive as a ubiquitous but unaccountable phenomenon. It is anything but unaccountable if the hypothesis is valid: the construct frames cruel, destructive, unempathetic behaviour, and transference of blame, in terms of the persistence, in the adult personality, of the predominance of infantile passive, egoistic motivation.

Narcissism is not just about the criminal of the tabloids; it’s about the real world: the human cost of the evils of capitalism, imperialism, militarism, settler-colonialism, elitism and racism. It’s about the intense suffering of millions of the most vulnerable at the hands of men whose arrested motivational development grants them license to behave manipulatively, ruthlessly and without compassion or remorse, as would any infant.

And that, I feel, is the gravity and the urgency of the case for research.